The Myths in our war films

What the German-made ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ reveals

by Jordan Rogers

March 20, 2023

All Quiet on the Western Front, the 2022 German feature dubbed in English, won four Oscars at the 95th Academy Awards. Along with Best International Feature, the production received three technical Oscars for its brutal war cinematography. While the battlefield scenes are thrilling, the film—produced by Germans and written by a German-born screenwriter—is uniquely illuminating for American viewers in other ways.

The original novel’s careful attention to psychological trauma is absent from this modern version (which was previously adapted on screen by Americans in 1979 and 1930), instead focusing on the random carnage of no man’s land between the trenches of the First World War. It’s a spectacular movie, with trench warfare depicted on a scale similar to what the famous opening action scene of Saving Private Ryan did for D-Day in World War II.

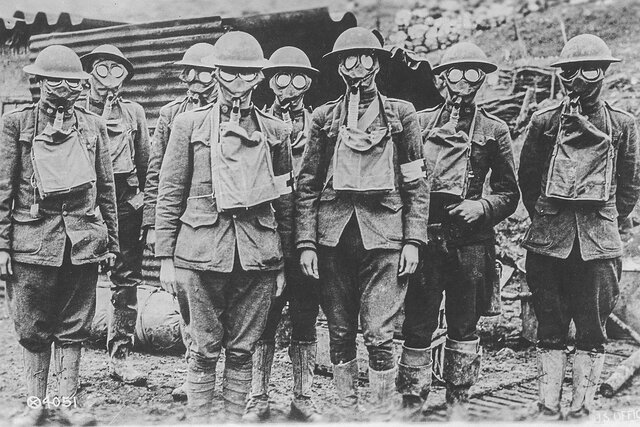

The extreme violence of the beach sequence of Steven Spielberg’s 1998 film—the chaos and horror of running exposed into open machine gun fire—is an apt primer for this new movie because much of the First World War was fought this way. All Quiet on the Western Front depicts what it was like to see Spielberg’s D-Day, every day, day after day, for four mind-numbing years. It is extraordinarily intense, and honest, showing the berserk barbarism of the world’s richest, most educated, and supposedly most civilized societies who for still ill-defined reasons chose to fire over a billion shells and twelve different types of poisonous gas at each other.

But raw adrenaline aside, this new film can answer questions about the world wars that even Spielberg can’t. It may not be the first English-focused blockbuster depicting wars fought by Germans, but it is the first made by Germans.

Native-made war movies are uniquely insightful, revealing much about societies and what they believe about their wars. Americans know their own war myths, and by virtue of history may know some British and French, but most do not know the German.

The German perspective on the two most formative geopolitical events in human history is particularly interesting, since they arguably started both.

For those who have waited for a full-scale feature film to explore the beliefs floating in the collective consciousness of the German people, that wait is over.[1] How might this film approach the war guilt of the Great War, the ancient rivalry with the French, the coming revolution that devolved into Nazism? The causes of all which remain contested.

War movies often unmask these stories and legends, tidbits and c-plots, guilt, pride, excuses and explanations of what nations think about their grandfather’s wars. It’s easy to see the American myths throughout Saving Private Ryan, where the plot itself is an alibi for entering a European war in the first place, thousands of miles from any home threat. Asked and answered explicitly in the film, the U.S. fought to do one decent thing in that “godawful, shitty mess”—to save Private Ryan, to be heroes.

Heroically liberating the French and defeating Nazism is certainly one reason America fought Hitler. But there are others. America’s economic calculations in the 1940s consistently aligned with its moral reckonings throughout the conflict. Both justifications have some truth of course, and that’s part of the myth making in war movies, writing plots about saving Private Ryan, leaving out the parts about securing shipping lanes across the Pacific Ocean or keeping Western European markets free from communist tanks.

The British have their myths too. Americans may not have known they were getting a healthy dose of British war mythology while watching 2017’s Dunkirk, produced and directed by Englishman Christopher Nolan, which he conceived during a trip across the channel on the same route of the famous evacuation.

One myth might be to even call it an “evacuation” when it wasn’t much more than a full-throttle retreat. The “Miracle of Dunkirk” may be that it is celebrated as a victory instead of the humbling defeat it was at the time.

Nolan isn’t shy about this. The main character tosses his rifle and flees in the opening scene, then spends the first act skipping ahead of his comrades to sneak on board a departing hospital ship, while French rearguard troops defend the beach under fire as the British evacuate. The only French character with lines saves Harry Styles’ life twice, before eventually sacrificing his own as his British friends escape once again. The message isn’t subtle.

Thousands of Frenchmen laid down their lives protecting the pocket around Dunkirk so the British could evacuate a quarter million of their troops back to England. Thousands of French were saved too, but there’s still soreness between both countries.

There is still soreness even between the British. The army was furious with the air force for seemingly leaving them like sitting ducks on the beach. The first clear line of dialogue (in a movie with very little) is a British soldier covered in sand after a dive bomber attack screaming “Where’s the bloody air force?!”

Nolan spends nearly a third of his movie countering this myth, taking care to show Tom Hardy’s character choose to run out of fuel and accept capture by the Germans to continue dogfighting. Near the ending, one soldier yells at a pilot, “Where the hell were you?!”—a question that makes little sense within the plot (the movie shows the RAF did fight over the beach and troops cheered the sight), only in the context of British and French history of the war is the meaning clear. As an elderly man[2] comforts the pilot on screen it’s as though Nolan used his film and its $150 million budget just to soothe old wounds between friends.

The historical truth of Dunkirk is the British were holding back some men and planes for the defense of their homeland, like any nation would. But there were British planes fighting over the beaches, the RAF lost more than 900 planes over France in the middle of 1940. The British Expeditionary Force buried 60,000 troops there that summer. There was no cowardice from the British at Dunkirk, nor from the French, who sacrificed maybe a hundred thousand men against the Germans throughout the Battle of France. But myths remain.

If Nolan’s film salutes French sacrifices, the German All Quiet on the Western Front is less forgiving to their neighbors. The film makes a point to show Marshal of France Joseph Joffre scolding a subordinate over a day-old croissant that lacks appropriate freshness for the allied general’s taste, unmoved as he hears of starving civilians from the German delegation meeting at Compiègne.

The armistice scenes at Compiègne in the 2022 film are, conspicuously, the only new storyline added from the book’s original narrative. Compiègne, surrounded by the forests of northern France, holds profound significance to Germany’s understanding of both wars, where the first’s infamous terms were signed, and where Hitler would later humiliate the French in 1940 in the exact same railcar.

Enormous scholarship has gone into studying, debating and understanding the connection between those two events, in the same train coach two decades apart, and perhaps in that context it makes sense the filmmakers decided to depict Compiègne at all. It adds little to the overall plot. But anyone interested in German war myths might pay close attention to what’s communicated in these revealing scenes.

In the movie, the German delegation stresses the need for a quick armistice to save human life. The French are aloof and unimpressed, and will not compromise on a total capitulation. The Germans plead for the French to be fair. Joffre scoffs at the idea of being “Fair?” considering the war waged by the Germans—who were the first to use gas, who were the first to torpedo civilian ships, and who literally started the war, a war fought on French soil ravaging French peasants. None of this is stated, though, all of it must be inferred from Joffre’s cert reply.

But the myth depicted in the movie is unambiguous: the French were unfair, the armistice terms were draconian, the peace agreement would be a “hated peace” as the lead German delegate says. One doesn’t need a history degree to imagine what that hate might precipitate in the years to come, or a psychology degree to understand why Germans would highlight the harshness of the Treaty of Versailles or the French attitude at Compiègne.

More explicit is the depiction of the military’s reluctance to accept the surrender, shown in several scenes, once with the visible hesitation of the army’s representative to sign, another referring to the agreement as a “pile of shit.” Historically, this is ridiculous, since it was the German generals who ultimately asked for an armistice. Their army was undoubtedly defeated militarily after the 1918 spring offensive failed to knock the allies out of the war before American soldiers and equipment began pouring into France.

But the filmmakers of course are just accurately portraying the imagined myth, perhaps the greatest war myth ever, that the Imperial German Army was neither defeated nor surrendered the Great War in 1918, a lie that directly precipitated the Stabbed-in-the-Back myth that proved so useful to the Nazis. A young Adolf Hitler would be attending his first German Workers’ Party meetings within a year.

The grand myth goes mostly unchallenged in the movie, though. One German field general condemns the armistice as “selling out our beloved fatherland,” before defying it with a final suicidal charge. The order shows he’s a monster, but his core claim is left uncontested. Perhaps that’s the intent. Or perhaps it’s a Freudian slip.

Much is open to the viewer’s own interpretation. In that sense the film is rich with other breadcrumbs. Every interaction between the main characters and the French is tantalizing, civilians and soldiers alike, at least for those of us across the pond who’ve never seen these European relations portrayed outside an art house film.

War myths don’t have to be true. In fact they rarely are. But they can still be informative and useful. Recognizing myths can help societies deal with and overcome the hidden falsehoods they nurture, something all nations with checkered pasts must learn and wade through still today. Americans certainly know this well.

Most nations have never much appreciated being reminded of their past mistakes. The new All Quiet on the Western Front offers the world a rare opportunity to watch the Germans toil with theirs.

§§§

[1]This is something I asked my European History professor (a German) about in my history program at UNC-Chapel Hill nearly twenty years ago. Like all college undergrads, I was tackling issues of how societies deal with their pasts, and was curious how Germans dealt with theirs. I asked Dr. Jarausch how WWI was remembered and discussed in German culture today. He said Germans don’t speak of it much, mostly due to embarrassment. One can imagine my surprise that, of the two world wars, it was the first which Germans might be most embarrassed.

[2]The older gentleman’s story depicted in Dunkirk is an accurate representation of the legendary real Charles Lightoller, the highest ranking officer to survive the Titanic disaster in 1912, who had a huge effect on maritime safety thereafter, who did sail his Sundowner yacht across the channel in June 1940, who did retrieve a stranded crew, and who did dodge a Stuka bomber on the way back carrying over a hundred soldiers. Not all legends are myth.

All images in this article are in the public domain.